(1879-1880)

In the first half of the 19th-century, Americans were absorbed with western expansion—fulfilling their “Manifest Destiny” to conquer the continent. By the 1870s, the interior of the country was secure, and the nation’s focus began to move beyond its borders, with increased emphasis on international trade. But global commerce was hampered by scores of competing coins and currencies, and many people on both sides of the Atlantic called for a worldwide coinage system to facilitate trade. In 1867, growing discussion blossomed into an international conference in Paris, where twenty nations agreed to adopt a gold standard with the French franc as its base.

Many in Congress envisioned the United States as the hub of a world monetary system and responded with their own ideas for an international gold coin, but few proposals went beyond debate. By 1871, it was silver, not gold, that was on the minds of many legislators, and silver was not faring well at all. Germany adopted the gold standard and dumped huge amounts of silver on the market, thereby depressing its price. At the same time, vast quantities of silver from the Comstock Lode added to the oversupply. With little industrial use for the metal, western mine owners desperately needed the U.S. Mint as a customer and in a big way. Fortunately, they got help from three very cooperative members of Congress, Representatives Richard Bland, John Kasson and William Kelley. For over two decades, these three never missed an opportunity to promote the interests of either silver or nickel mine owners, and they were often quite successful in their efforts.

Kasson and Kelley were partly responsible for conversion of the dime, quarter, and half dollar to the metric system in 1873. Although they argued that metric coinage would circulate worldwide and increase the demand for American silver, the change had little impact, either on the weight of the coins or their use overseas. The legislation did have a bonus for the mine owners, however: The silver interests got free coinage of a Trade dollar for use in the Orient. The Mint made almost 36 million of these large silver pieces between 1873 and 1885, barely enhancing commerce with the Far East but certainly adding to the mine owners’ bottom lines. The nickel interests also got a gift: With the elimination of the three and five-cent pieces made of silver, the Mint was limited to using nickel for those denominations. Five years later, the silver interests scored again: In 1878, Bland pushed through the Bland-Allison Act, requiring the government to purchase between two and four million ounces of silver each month and coin the metal into standard silver dollars.

It was Kasson, though, who was behind another try at an international coinage in 1879. Attempting to appease advocates of both silver and gold, he proposed a “goloid” dollar containing 96% silver, 4% gold, and a four-dollar gold piece of 90% gold, 10% silver. The four-dollar coin was intended to compete globally with a myriad of similarly valued pieces, including the French 20 franc coin, the Spanish 20 pesetas, the Dutch and Austrian 8 florins and the Italian 20 lire.

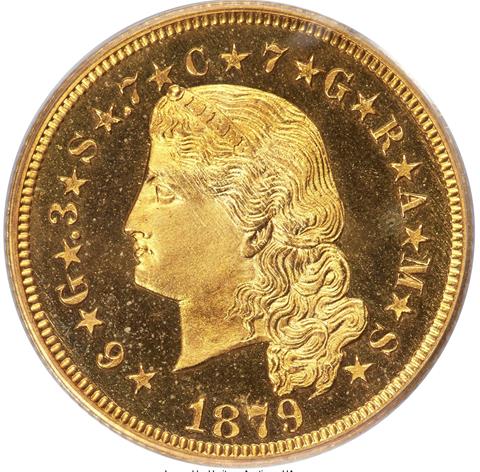

The four-dollar coin received an entirely new designation: “stella” (Latin for star). This was analogous to the eagle, “both the star and the eagle being national emblems on our coins.” Like the ten-dollar eagle and its smaller and larger counterparts, the stella was to be another denominational unit, and other coins would be expressed in fractions or multiples of it. Along with the stella, patterns for the “goloid” dollar and a “quintuple stella” (metric double-eagle) were struck in 1879.

There were two obverse designs for the stella—one with Flowing Hair engraved by Charles Barber and another with Coiled Hair by George Morgan. Barber’s design depicts Liberty with long, flowing hair; Morgan’s version differs only in that Liberty’s hair is tied in a bun. On both designs, Liberty is encircled by the lettering *6*G*.3*S*.7*C*7*G*R*A*M*S*, stating the proportions of gold, silver and copper in the coin. The reverse features a large five-pointed star as the central motif, with the incuse inscription ONE /STELLA/400/CENT. Both the U.S. motto E PLURIBUS UNUM and the Latin motto DEO EST GLORIA (God is Glorious) circle the star, in turn surrounded by the inscriptions UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and FOUR DOL.

The stella never saw regular production; Congress killed the legislation and only patterns were made, all proofs. Unfortunately, mintage records for these pieces have proven to be unreliable. Today, specialists believe that only 15 originals and 425 “restrikes” of the 1879 Flowing Hair design were made, with the originals lacking the die striations of the later pieces. These 1879 Flowing Hair “restrikes” are the most frequently encountered of this denomination, as all the other issues are exceedingly rare. Surviving 1880 dated Flowing Hair coins number fewer than 25, and the highest estimates of existing Coiled Hair pieces are 15 for the 1879 and 10 for the 1880 coins. Whatever the exact number, 1880 Flowing Hair pieces are at least a dozen times scarcer than their 1879 counterparts, and Coiled Hair stellas are rarer still, seldom appearing on the market except in sales of major collections.

Although all four-dollar gold pieces are patterns, they have nevertheless been incorporated into the regular series of U.S. coins, similar to 1856 Flying Eagle cents, Gobrecht dollars and Wire Edge Indian Head eagles. Because of their rarity, however, they are usually collected as type coins. Only a few wealthy and determined collectors have ever been lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time to put together a complete four-piece set of these historic coins. At the time they were made, stellas were very popular with collectors, but with the extremely low mintages, there were not enough pieces to go around. In the early 1880s, newspapers reported that while an average collector could not acquire a four-dollar gold piece from the Mint at any price, looped specimens could be seen hanging around the necks of madams operating some of Washington’s most famous bordellos.

Gem specimens of all four issues exist, but many stellas saw use as jewelry or pocket pieces and show impairments of some kind. Friction on the design will first show on the face of Liberty on the obverse and on the star on the reverse. Unlike the commonly traded bullion coins struck in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th-centuries, stellas are infrequently seen and always scrutinized, making counterfeits virtually unknown.

After two years, the four-dollar gold piece was abandoned by the Mint and forgotten by the public and Congress. Today, only numismatists remember the dream of a universal coinage system that created these fascinating coins.

Coin Descriptions Provided by Numismatic Guaranty Corporation (NGC)

(Less text)